Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) such as GPS, BeiDou, Galileo and GLONASS have become invisible infrastructure for modern society. They enable everything from smartphone maps and aviation navigation to autonomous drones and critical infrastructure timing. Yet GNSS signals arriving from satellites are extremely weak and therefore vulnerable to interference and deliberate jamming. In recent years, intentional jamming and spoofing events have increased in several regions, making GNSS resilience a strategic priority for both civil and military users.

Among the most effective ways to protect GNSS receivers is the use of GNSS anti‑jamming antennas. These specialized antennas are engineered not only to receive legitimate satellite signals but also to suppress interference in real time, ensuring that positioning, navigation and timing (PNT) services remain available even in hostile RF environments.

For organizations looking for practical, deployable solutions, manufacturers such as CHREDSUN provide complete GNSS anti‑jamming antenna families that can be directly integrated into existing platforms. More information is available at: https://www.chredsun.com

1. What Is a GNSS Anti‑Jamming Antenna?

A GNSS anti‑jamming antenna is a specialized RF front‑end designed to protect GNSS receivers from interference and jamming. Instead of passively accepting all incoming RF energy, an anti‑jamming antenna senses, identifies and suppresses unwanted signals, while preserving and often enhancing the desired satellite signals.

Key characteristics include:

Directional discrimination: the ability to treat signals differently based on the direction they arrive from, using spatial filtering and beamforming.

Advanced signal processing: the use of adaptive algorithms to detect interference patterns and place “nulls” in those directions, reducing jamming power before it reaches the GNSS receiver.

Multi‑constellation, multi‑band support: reception of multiple GNSS constellations and sometimes multiple frequency bands (for example L1/L2, B1/B3) to increase robustness and accuracy.

In many modern solutions, anti‑jamming capability is implemented as a combination of multi‑element antennas and digital signal processing units. Systems like Controlled Reception Pattern Antennas (CRPA) employ an array of antenna elements whose outputs are combined with specific weights to form a steerable reception pattern. This reception pattern can emphasize directions of desired satellites and de‑emphasize or null out directions of jammers.

For system integrators who want to explore practical hardware options, it is useful to review product‑level implementations, such as those presented on https://www.chredsun.com, where different form factors and element counts are compared.

2. Why GNSS Anti‑Jamming Matters Today

GNSS signals at the Earth’s surface are extremely weak—on the order of –130 dBm or lower. Even a low‑power jammer can raise the noise floor dramatically and make legitimate satellite signals indistinguishable from interference.

Several trends make GNSS anti‑jamming a critical topic:

Rising intentional jamming and spoofing events: airports, maritime corridors and conflict zones have reported increased interference incidents, threatening safety‑critical operations.

Growing reliance on autonomous and remotely operated systems: UAVs, ground robots and autonomous vehicles depend heavily on GNSS for navigation, especially beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS).

Critical infrastructure dependency: power grids, telecom networks and financial systems rely on GNSS‑based timing; loss of GNSS can affect stability and synchronization.

Anti‑jamming antennas help mitigate these risks by improving the signal‑to‑interference‑plus‑noise ratio (SINR) at the front end, giving downstream receivers a much cleaner input to work with. This is one reason why more UAV and infrastructure projects are now actively searching for anti‑jamming hardware vendors via channels such as dedicated product sites (for example, https://www.chredsun.com).

3. Core Technologies Behind GNSS Anti‑Jamming

Several complementary technologies are commonly combined in advanced anti‑jamming antenna systems:

3.1 Spatial Filtering and CRPA

Controlled Reception Pattern Antennas (CRPA) use multiple antenna elements arranged in an array. By adjusting the phase and amplitude of each element’s signal, the system can steer the main reception lobe towards desired satellites and create deep nulls in the directions of jammers.

Beamforming: enhances desired signals by pointing the antenna’s reception pattern towards them.

Null steering: places deep minima in the pattern towards interfering sources, reducing jamming power reaching the receiver.

The more elements in the array, the more degrees of freedom are available to place multiple nulls while still maintaining gain towards satellites.

3.2 Signal Processing and Adaptive Filtering

Anti‑jamming systems increasingly rely on digital signal processing (DSP) to analyze incoming signals, detect abnormal patterns and adapt the antenna’s response.

Typical functions include:

Jamming detection: monitoring metrics such as SNR, noise floor, and spatial distribution to identify the presence of interference.

Adaptive filtering: dynamically adjusting filter coefficients in time, frequency or space to suppress jamming energy while preserving GNSS signals.

Spoofing awareness: in some systems, angle‑of‑arrival and consistency checks help distinguish genuine satellites from spoofers.

3.3 Polarization and Radiation Pattern Design

Careful control of antenna polarization and radiation pattern also contributes to anti‑jamming performance.

Matching GNSS polarization (typically RHCP) improves reception of legitimate signals.

Pattern shaping can reduce sensitivity to low‑elevation ground‑based jammers while maintaining gain towards high‑elevation satellites.

4. Inside a 16‑Element GNSS Anti‑Jamming Antenna

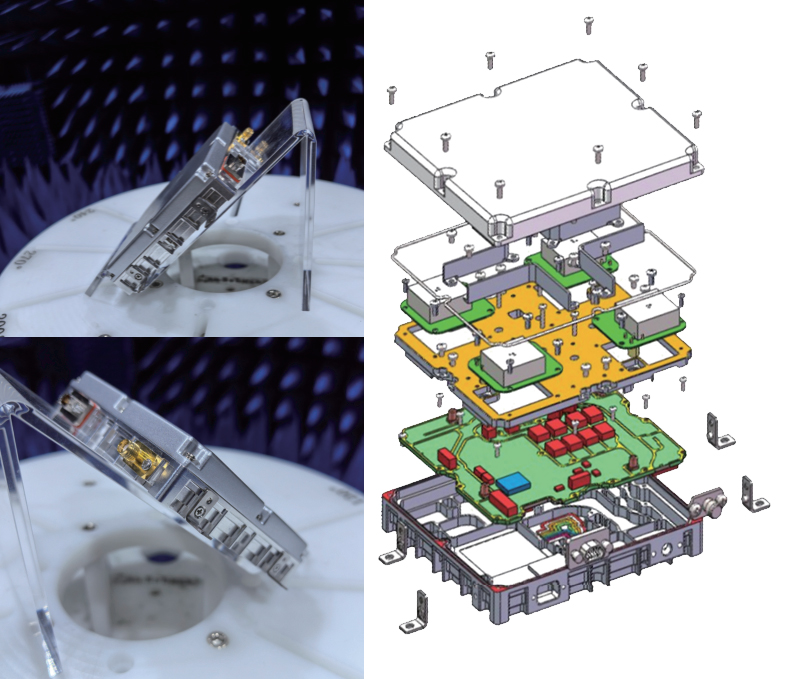

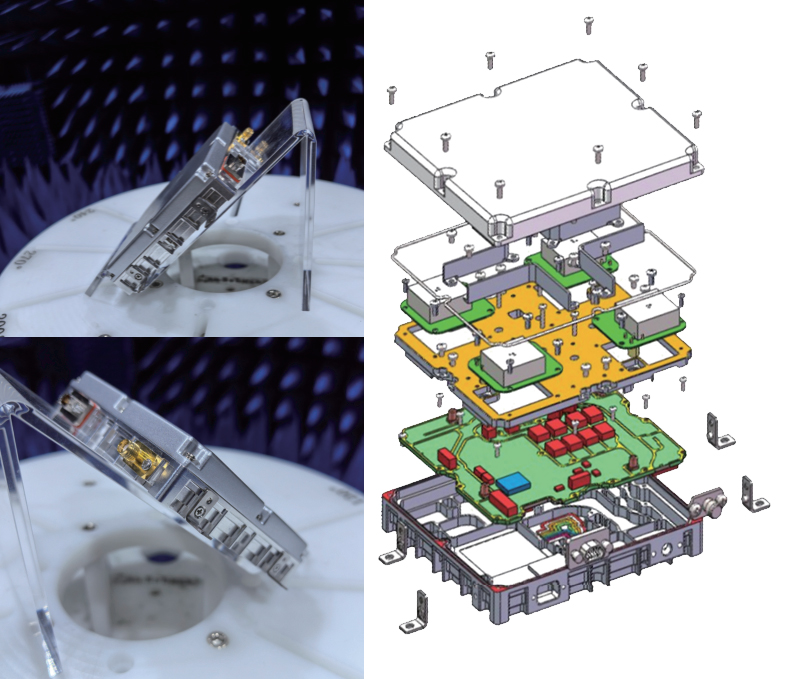

To understand how these ideas are realized in a practical product, consider a 150×150 mm 16‑element anti‑jamming antenna module, similar in design to the solutions presented by CHREDSUN.

4.1 Structural Composition

Such an antenna module typically integrates several subsystems in a rugged housing:

16‑element antenna array arranged within a 150 × 150 mm aperture to collect signals from multiple constellations and bands.

Low‑noise amplification and down‑conversion stages, ensuring that weak satellite signals are amplified while preserving their integrity for processing.

Anti‑jamming processing unit, which implements spatial filtering and null steering against multiple interferers.

Optional integrated GNSS receiver, capable of computing position and velocity, so the unit can operate either as a smart anti‑jamming front‑end or as a complete PVT source.

Rugged mechanical enclosure with outdoor‑grade environmental protection, designed for harsh field conditions.

On CHREDSUN’s website (https://www.chredsun.com) integrators can see how different anti‑jamming antennas are packaged, including details on housing, mounting options and connector layout, which simplifies mechanical and electrical design.

4.2 Supported GNSS Modes and Signals

A 16‑element array in this class is usually compatible with multiple constellations and signals, for example:

BeiDou (BDS), GPS, Galileo and extended GLONASS support.

Signal combinations such as BDS_B1C/B1I, GPS L1 C/A, Galileo E1 and optional BDS B3.

This multi‑constellation, multi‑signal capability enables higher availability and accuracy, especially when jamming reduces the number of visible satellites on a given frequency.

4.3 Anti‑Jamming Capability

A high‑end 16‑element GNSS anti‑jamming antenna is engineered to handle complex interference scenarios:

Jamming types: broadband, narrowband, frequency‑sweeping, pulse and combinations thereof in the key GNSS bands.

Number of jammers: suppression of multiple jamming sources arriving from different directions at the same time.

Jamming‑to‑signal ratios: deep J/S margins, so that even when interference power is many tens of dB stronger than the desired satellites, the system can still keep tracking.

The protected airspace typically covers 360° in azimuth and a wide elevation angle, so interference can be mitigated from almost any direction around the platform.

4.4 RF and Receiver Performance

On the RF side, such an antenna provides:

When a built‑in receiver is used, typical performance includes meter‑level position accuracy and decimeter‑per‑second velocity accuracy, sufficient for many UAV and infrastructure applications. Solutions shown on https://www.chredsun.com illustrate how this is delivered in a fully integrated module.

4.5 Power, Mechanical and Environmental Design

For integration into diverse platforms, key design points include:

Wide DC input range (for example 9–36 V) to match vehicular and aviation power buses.

Moderate power consumption compatible with UAV and mobile platforms.

Rugged mechanical design with IP‑rated sealing, corrosion‑resistant housing and standard mounting interfaces.

Such attributes allow deployment on airframes, ship decks, ground vehicles and fixed masts with minimal adaptation.

5. Advantages of Multi‑Element GNSS Anti‑Jamming Antennas

Compared with traditional passive GNSS antennas, multi‑element anti‑jamming arrays offer several distinct advantages.

5.1 High‑Order Spatial Filtering

With many elements, the system has enough degrees of freedom to place multiple spatial nulls while still maintaining gain towards satellites. This allows simultaneous suppression of multiple jammers, a capability far beyond single‑element antennas with fixed patterns.

5.2 Full‑Sky Coverage

The ability to mitigate interference across the full azimuth and a wide elevation range means that both ground‑based and airborne jammers can be addressed. In practice, this is critical for UAVs or maritime platforms that may encounter interference from different heights and directions.

5.3 Integrated Receiver Option

By embedding a GNSS receiver inside the antenna module, the system can serve as either:

A drop‑in anti‑jamming front‑end feeding an existing receiver, or

A self‑contained PNT unit providing position and velocity over a data interface.

This flexibility simplifies system design and enables different architectures depending on end‑user needs. For example, some products showcased on https://www.chredsun.com can output both RF and processed navigation data, giving integrators multiple design choices.

5.4 Rugged, Ready‑to‑Integrate Form Factor

The compact footprint, moderate height and robust environmental protection make modern anti‑jamming antennas suitable for many platforms. The wide input voltage range and standard connectors further reduce integration effort and time‑to‑market.

6. Key Use Cases and Deployment Scenarios

GNSS anti‑jamming antennas are increasingly deployed in both military and civilian domains. Typical scenarios include:

6.1 Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs)

Industrial and tactical UAVs rely heavily on GNSS for navigation, georeferencing and return‑to‑home capabilities. In areas with known interference or high‑value targets, jamming can cause:

Loss of navigation,

Mission aborts,

Drift in survey data, or

Unsafe flight behavior.

A multi‑element anti‑jamming antenna allows the UAV to maintain satellite lock and stable navigation even when deliberate jamming is present, making it ideal for:

Long‑range mapping and surveying missions,

Infrastructure and pipeline inspections,

Border surveillance and security patrols,

Tactical reconnaissance flights.

UAV manufacturers and integrators exploring these capabilities can review example antenna configurations, mechanical drawings and electrical interfaces on supplier sites such as https://www.chredsun.com.

6.2 Aviation and Rotorcraft

Aircraft rely on GNSS for navigation, performance‑based navigation procedures and as part of redundancy for traditional navigation aids. Anti‑jamming antennas protect against interference near airports, along certain routes and in regions with elevated GNSS threat levels.

6.3 Maritime and Offshore Operations

Ships, offshore platforms and autonomous surface vessels use GNSS for navigation, dynamic positioning and timing. Interference in busy sea lanes or near sensitive facilities can have serious safety and economic implications.

Deploying anti‑jamming antennas on these platforms helps maintain precise positioning even when exposed to intentional or unintentional jamming sources.

6.4 Critical Infrastructure and Ground Systems

Many critical facilities depend on GNSS for timing, including:

Installing anti‑jamming GNSS antennas at these sites reduces the risk of timing loss due to jamming, supporting overall system resilience. Integrators responsible for these systems can find ready‑to‑deploy antenna modules and documentation on GNSS hardware vendor websites such as https://www.chredsun.com.

7. Outlook: The Future of GNSS Anti‑Jamming Antennas

As GNSS interference becomes more common and more sophisticated, anti‑jamming antennas will continue to evolve in several directions.

7.1 Higher Integration and Intelligence

Future systems are expected to integrate:

Multi‑band, multi‑constellation support with even more flexible frequency coverage,

On‑board analytics for interference characterization and threat reporting,

Tight coupling with inertial navigation systems (INS) to bridge GNSS gaps.

Antennas may increasingly be delivered as full PNT modules combining RF front‑end, anti‑jamming processing and navigation engine.

7.2 Compact Multi‑Element Arrays

Advances in RF design and miniaturization are enabling smaller multi‑element arrays suitable for compact UAVs and vehicles. Solutions with 16 or more elements in relatively small footprints are becoming more accessible for wider classes of platforms.

7.3 Wider Civil Adoption

Originally driven by defense applications, GNSS anti‑jamming is now spreading into:

This broader adoption will likely lead to greater standardization, improved cost profiles and more accessible solutions for integrators. Vendors that already serve both defense and civil markets, like those reachable via https://www.chredsun.com, are well positioned to support this transition.

8. Conclusion

GNSS anti‑jamming antennas are becoming essential components in any system that depends on reliable satellite‑based positioning and timing. By combining multi‑element arrays, spatial filtering, advanced signal processing and rugged mechanical design, modern solutions can suppress multiple jamming sources while maintaining accurate navigation information.

For UAV manufacturers, system integrators and infrastructure operators facing growing GNSS threats, deploying such anti‑jamming antennas is a practical and powerful step toward resilient PNT in contested environments. Readers who want to explore concrete hardware options, mechanical drawings and integration guidelines can visit https://www.chredsun.com to review product‑level specifications and discuss custom solutions with the engineering team.

English

العربية

Français

Русский

Español

Português

Deutsch

italiano

日本語

한국어

Nederlands

Tiếng Việt

ไทย

Polski

Türkçe

አማርኛ

ພາສາລາວ

ភាសាខ្មែរ

Bahasa Melayu

ဗမာစာ

தமிழ்

Filipino

Bahasa Indonesia

magyar

Română

Čeština

Монгол

қазақ

Српски

हिन्दी

فارسی

Kiswahili

Slovenčina

Slovenščina

Norsk

Svenska

українська

Ελληνικά

Suomi

Հայերեն

עברית

اردو

Afrikaans

Gaeilge

नेपाली

Aymara

Беларуская мова

guarani

Krio we dɛn kɔl Krio

Runasimi

Wikang Tagalog